Life On The Run

No lawyer. No phone call. Nobody knew where I was. Home was a cell in the Cook County Jail.

I was maced, clubbed, and thrown in a paddy wagon. Dozens of us were smashed together, heaving from teargas, bruised, and weirdly triumphant. We got what we wanted. To be beaten and arrested.

A woman who saw how distressed I was cradled me in her arms. I have a party to go to Friday night, I told her. Do you think I’ll get home in time? She looked at me with loving, adult eyes — she must have been 22, five years older than me — that conveyed pity and sympathy. You poor boy, she said, holding me tighter. She was blinking wildly from the mace. Tears streamed down her cheeks and mixed with the blood from her busted lip.

We were separated, shackled, and led into jail. I was wheezy through it all, nauseous, disoriented, and pushed along. I sat before a bored and irked cop who complained that they called him in on his day off to book us. He was home watching a football game an hour ago, and here he was filing a complaint that said he saw me rioting and resisting arrest. He filed the same bogus report for nine others.

They threw me in a holding cell with a crush of other protestors. Then they took me before the judge. “Is this a boy or a girl?” the judge asked the prosecutor. “Unfortunately, your honor, it’s a boy.” The judge shook his head in dismay. “What are the charges?” “Crossing state lines to incite a riot. Mob action. Disorderly conduct,” said the prosecutor. That was alright with the judge. He slapped me with two felonies, a misdemeanor, and $10,000 bail. They cuffed me, led me away, and then shaved my long hair to make sure I looked like a real boy.

No lawyer. No phone call. I left Brooklyn without telling anyone where I was going. Nobody knew I was in Cook County Jail in Chicago. As far as my mother knew, I simply disappeared.

My new home was a two-person cell. I was the third person, so I slept on the floor under a worn-out Army blanket. A bare lightbulb shone in the cell 24/7. A guard with a gun patrolled. I watched a rat skitter down the concrete hallway.

Dinner was slop and a hard biscuit on a tin tray. A TV in the corner showed the news of the riots and a cheer went up, raised fists. We made news. This cell block was full of Weathermen who came to Chicago to riot. The intent was to bring the war home and create havoc on the streets of America until we got out of Vietnam.

JJ (John Jacobs) jumped on a table. We’re going to fill the jails, he said. His voice was a bullhorn. He was yelling like Fidel to the troops, ready to storm Havana and topple the government. We’ll shut down the criminal justice system. The workers will join us. All great revolutionaries spend time in jail. We will have a popular uprising in America. Bring the war home. He quoted Che Guevara: “… I will take to the barricades and the trenches, screaming as one possessed,.”

I listened to JJ from a distance, cocooned in a ratty wool blanket. It was a posture I found comforting. I was attracted to these extreme situations, these vanguard experiences, and yet I wasn’t part of them. I wanted to be an outsider on the inside. And now I found myself inside what I didn’t realize was one of the toughest jails in America. Cook County. Just the name sounded tough.

For a couple of days, we reveled in our pyrrhic victory. It was a reflex mechanism. We expected tens of thousands to come from all corners of the country to spark a popular uprising. Instead, we got a couple hundred from the hardcore collectives and a gaggle of gullible high school recruits, like me.

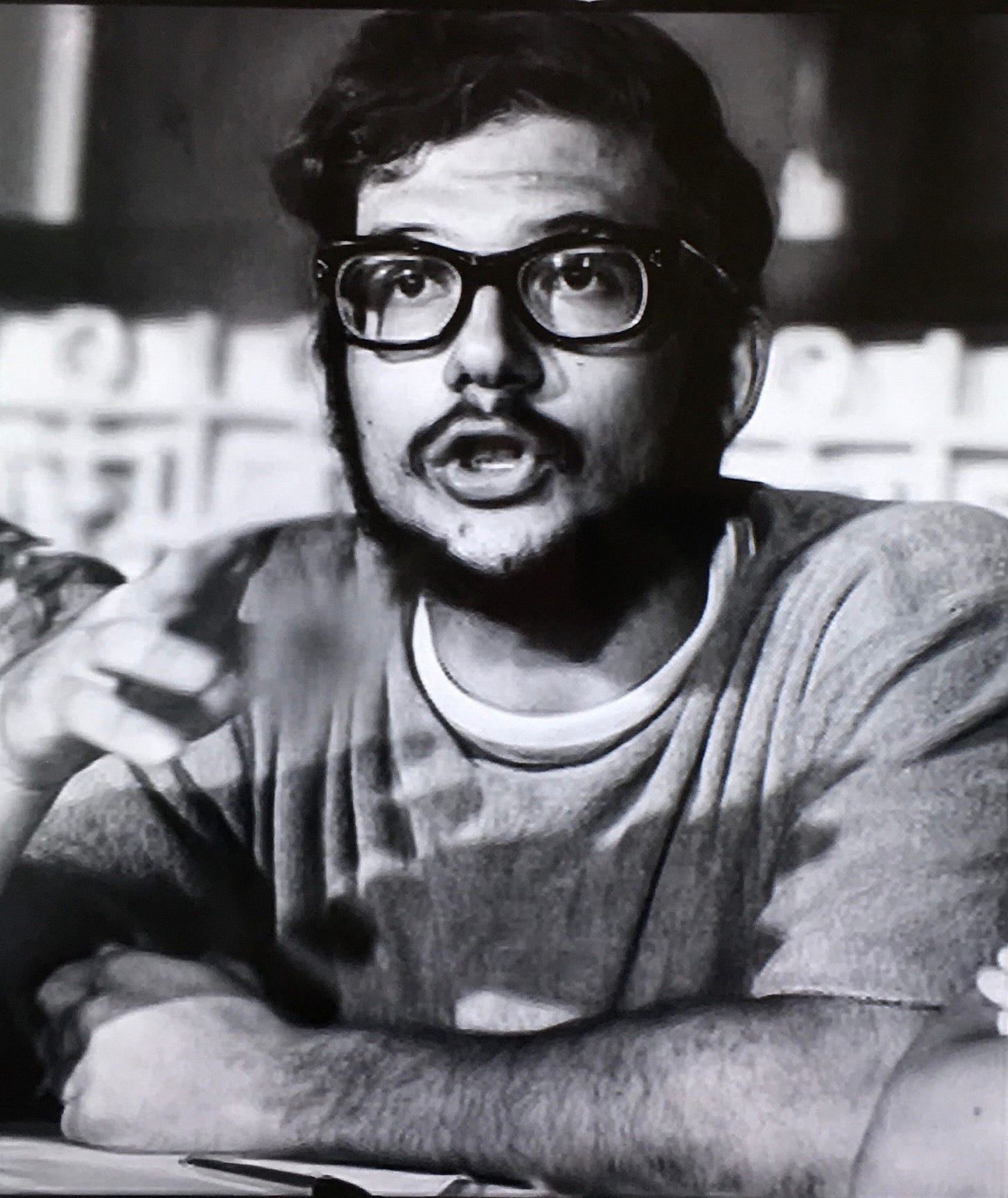

Ted Gold recruited me when I was 16. Unlike the bombastic, scene-chewing JJ, Ted was bookish and empathetic. He appealed to my sensitivity and my deep pain at injustice. He was a Columbia grad and vice chair of SDS. His father was a doctor; both his parents taught at Columbia. Ted was headed for a career in academia, following the path of his left-wing upper-west Jewish family, when the movement swept him up and he became an unlikely leader.

Ted was 21, an adult, a brother, and a father figure to fill in for my absent biological father. Barely a week after my 17th birthday, I flew to Chicago to riot because Ted convinced me it was the right thing to do. Unfortunately, Ted was not in this cell block. I didn’t have friends among the leadership or the rank and file. I was an outsider on the inside, caught up in the fervor of an uprising that no one knew about.

I was a lousy revolutionary. When it came time to run wild through the streets, smashing windows, and causing mayhem, I couldn’t do it. I could run with them but I couldn’t be the instigator of violence. I was on the receiving end of tear gas and mace and the crunch of a nightstick on the backside of my legs. That was the price you paid to be in this family.

JJ went on and on. We demand lawyers. We demand that all political prisoners be freed. JJ was making a lot of demands until three burly / surly-looking guys came in with shotguns and took him away. No leaders here, one of the surlys said. You’re prisoners. If anybody thinks otherwise, you go to the hole. That quieted the cellblock.

I cocooned in the wool blanket in a fetal position on the floor of my cell. I’d developed an uncanny ability to sleep anywhere, almost on command. There was a ruckus all around me, bare lightbulbs shining, cell doors clanging, people chattering, and I slept through it, curled into myself. I had anemia, and I let it take over, rendering me somnolent. I developed this ability after my parents divorced when I was 15, and I unconsciously decided, unfettered by parental control, that I would rebel against anyone and everything in the most flagrant ways possible while maintaining my singular defensive shell.

After four days in jail, I started to feel weak and slightly feverish. It was a familiar and welcome feeling. I was a sickly child. I caught whatever was going around and ran high fevers. I was in and out of hospitals with various maladies and came to enjoy the attention and care. Sleepy and subdued, I was able to shut out the world. Nothing could penetrate. Fatigue became my norm.

One day, a priest and a Rabbi were allowed into the cellblock to bring spiritual comfort to us poor prisoners. I sat down with the Rabbi and told him my story. He smuggled out my mother’s phone number. A day later, the Rabbi bailed me out.

He took me to his home in Evanston. I had a shower, and I sat down with his family for dinner. Then the questioning started. What on earth was I thinking coming to Chicago to riot? What could breaking windows and running wild through the streets possibly accomplish? I spouted the standard lines about the workers’ revolution and rising up against imperialism and racism, stopping the war, etc. The Rabbi looked at me with disbelieving eyes and shook his head. Was I ever so sure of anything as I was when I was 17?

Back Home

The next day, I was on a plane back to New York. When I got to the apartment in Brooklyn, my mother felt my forehead and ordered me to bed. She made me chicken soup. I was running a 103 fever. I slept for a full day.

The apartment felt empty, rooms with no people, its own sort of prison. My father bailed and married a cocktail waitress 20 years younger and he had a new life with a new family in Queens. My brother Bruce was in college in Arizona, and my sister Bonnie was in California. My older brother, Dennis, recently returned from a one-year combat tour in Vietnam and was readjusting, unsuccessfully, in Staten Island. He arrived in Vietnam with the 1st Air Cavalry just in time for the Tet Offensive. At the time, I didn’t see the irony in that, considering my predilection, nor did I have any awareness of what he might have gone through. The chaos of the world filtered through my adolescent despair. I was more sympathetic to the masses than to my grief.

When I woke from my feverish stupor, my mother was sitting on a chair, staring at me, her poor, sensitive baby son, who was trying to save the world.

At that moment, I realized that I got what I wanted: my mother’s undivided attention.

I asked a lot of my mother. She was the first-generation daughter of immigrants who fled Russia to escape the pogroms (organized massacres of Jews). Assimilation was key for her generation. She wasn’t Jewish or Russian. She was American. She wanted the car, the home, the money, all the finery and freedom that being an American afforded. You respected authority, you didn’t question the government, you got an education and a career, and you made a living. You fit in. That’s what it took to be an American.

I rejected all that, which made me a lone wolf in the family. No one else shared my views or could understand my seemingly self-destructive behavior. I asked unanswerable questions - like why do we have to kill these people nine thousand miles away? I will never, under any circumstances, enable that or be drafted into that horror story.

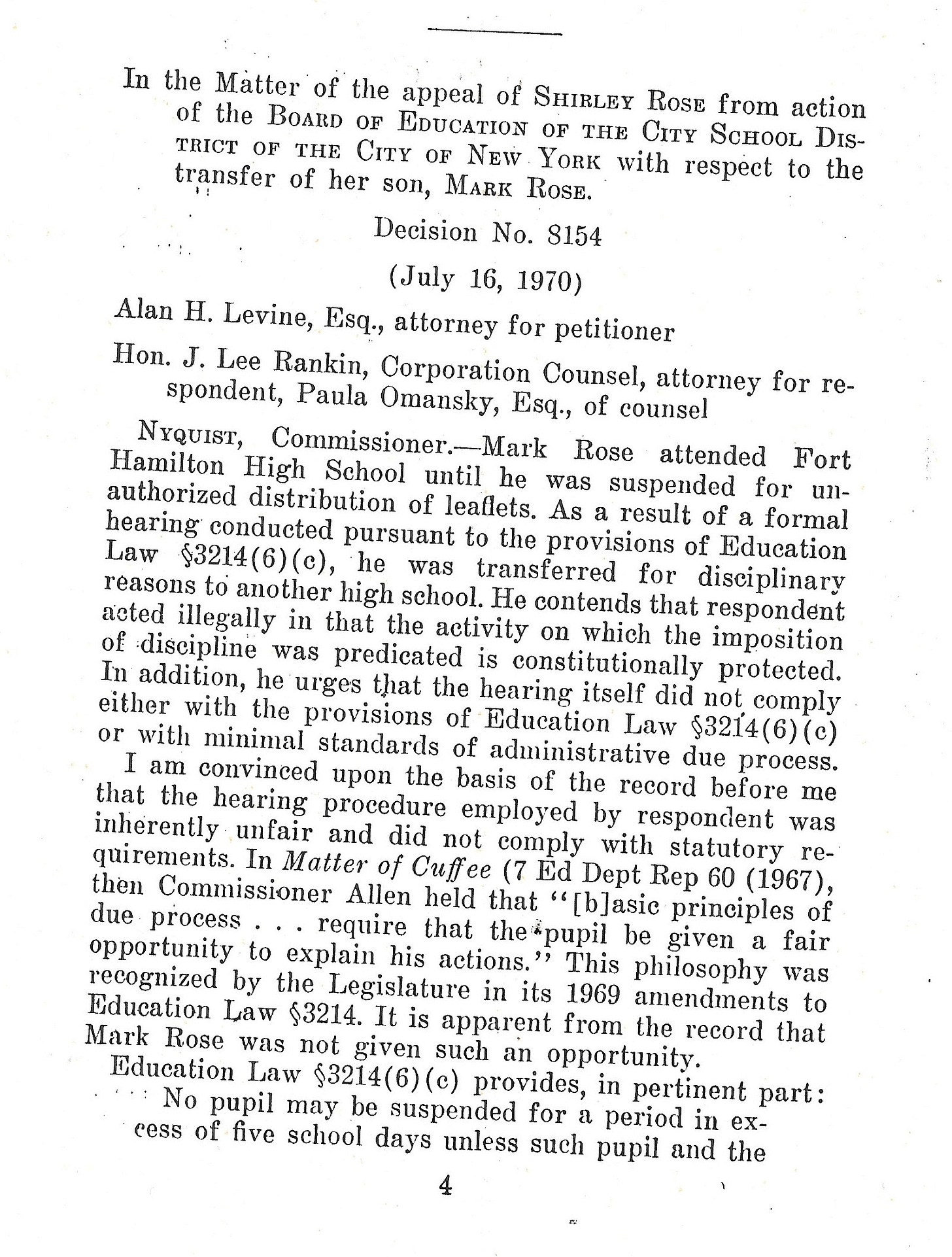

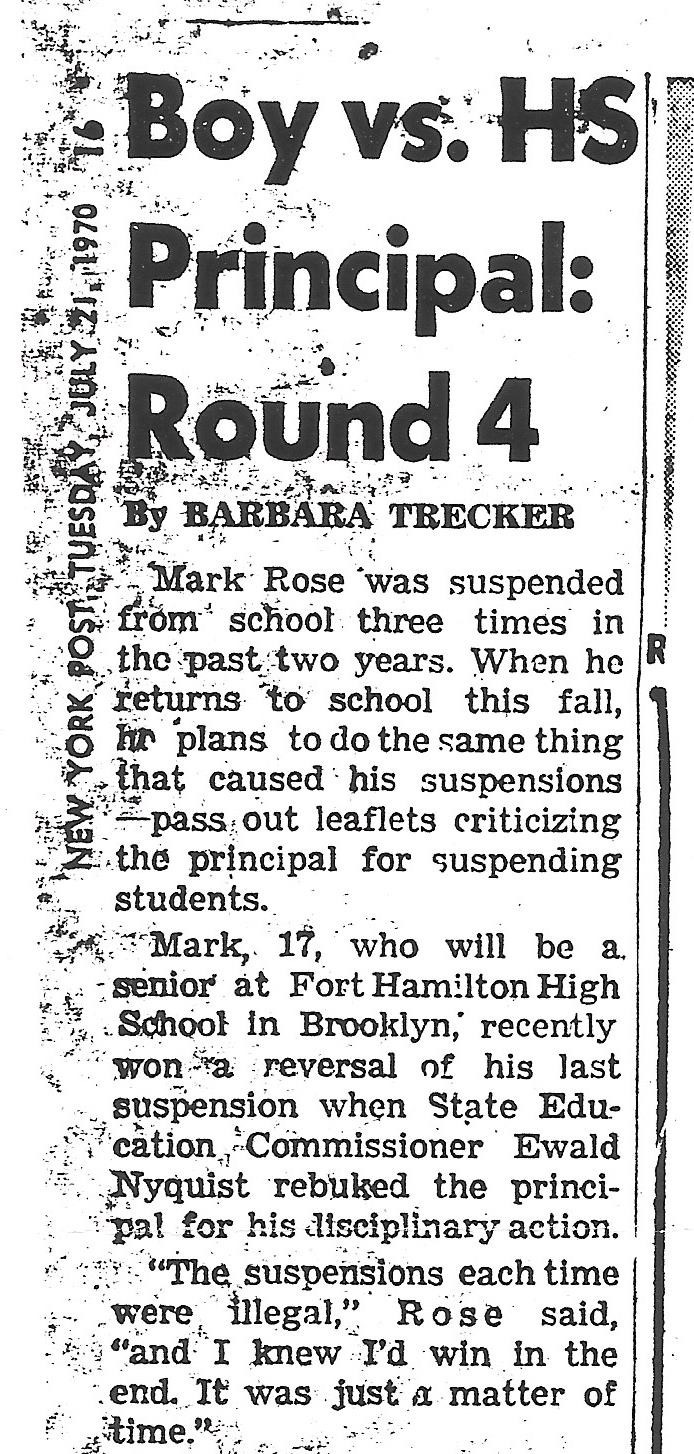

When I transferred from Brooklyn Tech to Fort Hamilton, the local Bay Ridge high school, the Vietnam War rapidly escalated. A draft was initiated, and I was coming of age. I was scared and angry. I vowed to bring the anti-war movement to my new high school. I found the perfect antagonist in the Fort Hamilton High School principal, Jon B. Leder.

Leder lorded over the high school, physically and vocally. He was imposing and strict. It was his domain. I challenged him by handing out anti-war leaflets to students going into class. He reprimanded me. I did it again. This time, he suspended me. I did it again. He suspended me again.

Each of these suspensions was accompanied by a good talking to. He’d get me in his office, close the door, and he started with the manipulation and intimidation. He threatened to mar my permanent academic record that would follow me to the grave and ruin my life forever if I didn’t stop my activities. He had his red pen out. Go ahead, I said. I didn’t like to be threatened, and I couldn’t imagine anything in the future being as important as this moment in my young life. This symbol of authority before me had to be confronted.

Leder summoned my mother and me to a conference in his office. He was imperious and condescending. She thought he was nuts, and he gave her a headache. I thought of Captain Queeg from the Caine Mutiny. At least my mother knew what I was up against, not that she condoned my activities. At least get out of high school, she’d say. Wait for college to protest.

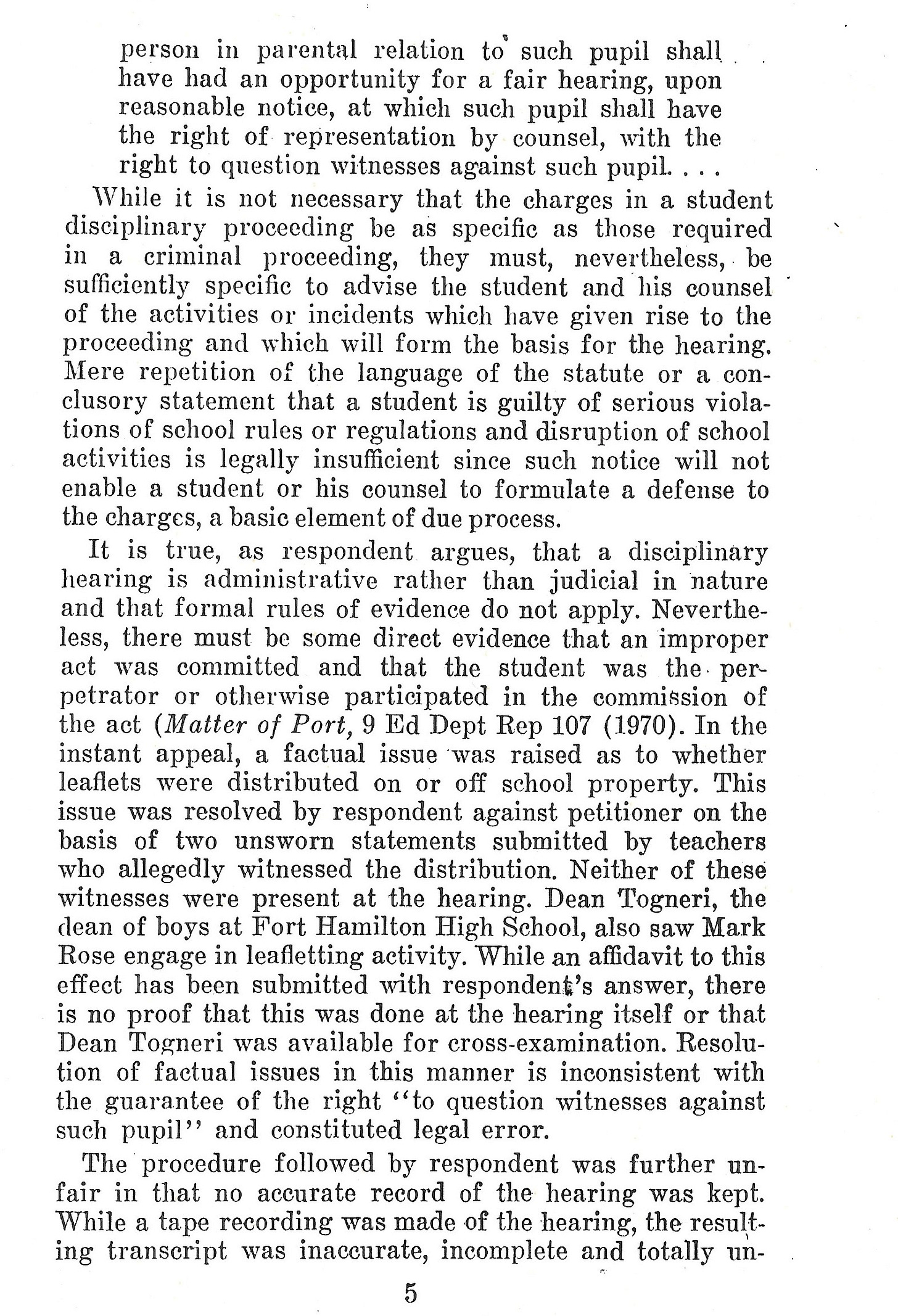

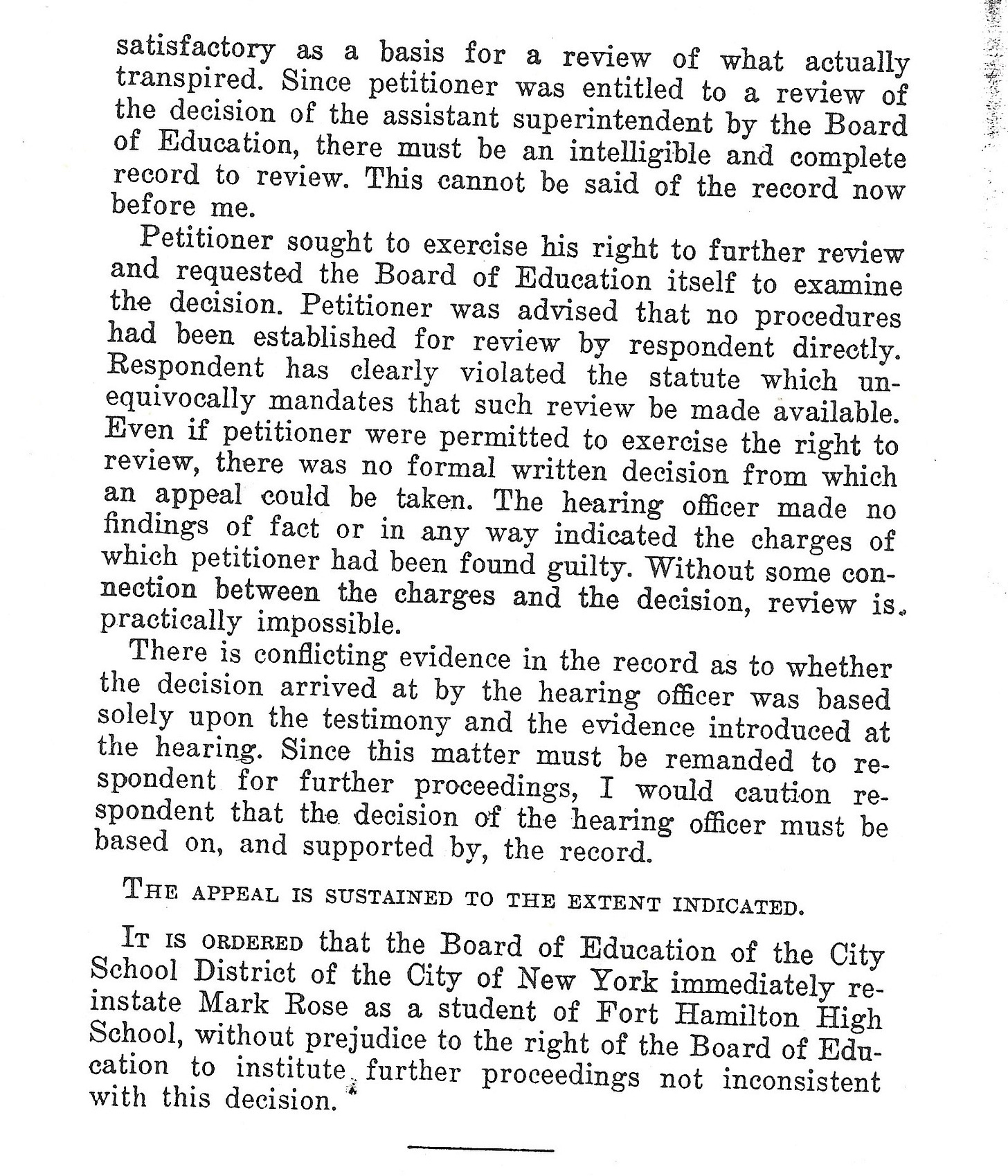

I was off school grounds when I handed out the leaflets, and I knew I was within my rights. The New York American Civil Liberties Union started a high school division and I became one of their test cases. With the backing of lawyers, certain of my rights, I handed out leaflets again and was suspended for the third time.

As punishment, Leder shipped me off to F.D.R. High School so I could be someone else’s problem. I spent a couple of days there and determined I didn’t like it. Then they shipped me off to New Utrecht High School. It was interesting to get an inside tour of Brooklyn high schools and I could keep going with this charade but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was being unfairly punished.

Leder told me that his word was final and there was no avenue to appeal. He was wrong, my lawyers told me, and we appealed to the New York City Board of Education. My mother had to sign the appeal since I was a minor. She was impressed by my lawyers. She didn’t know what I was doing or why I was doing it, but she felt important. It gave her something to gossip about and she enjoyed the attention.

A meeting was set up at that dreaded fortress on 110 Livingston Street (how many times had we protested outside that building?). The hearing was a sham. Leder spouted some nonsense, the “examiner” backed him up, and they pretended to take a record of the proceedings.

We decided to appeal to the New York State Education Commissioner. That took time. I opted to stay out of school and spend my days on the streets protesting and working on my case.

I got a great education when I was out of high school. I went to Harvard, Yale, Columbia, NYU, and Georgetown. I saw those pillars of higher education through the haze of tear gas, usually confronted by a phalanx of police and National Guard. I joined the High School Student Union in New York and wrote for the High School Free Press. I got a job pushing hot dogs at Nedick’s outside the 86th Street subway stop in Brooklyn. That’s how I earned the money to fly to Chicago.

Ted Gold was in this room.

My bedroom was sanctified by his presence. Ted sat in a lotus on the blue shag carpet and schooled me on the revolution. Ted had been around. He was in Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade. He worked with North Vietnamese, cutting sugar cane. He was heavy-duty, he was smart, and he was on a mission to recruit disillusioned high school students. He was trying to relate to the counterculture with awkward ‘hip’ slang, but he was from a different class, the intellectual class, Manhattan. He liked to smoke pot but that only led him down a semantic rabbit hole that swirled around communist propaganda. Ted was part of the collective in New York. I was impressed that he took the R train to the end of the line, the last stop in Brooklyn, and walked seven blocks to get to our apartment. We were in a six-story apartment building in a secluded spot along Shore Road. Many a night I walked along the promenade in darkness, the moon glinting off the Verrazano Narrows. That beautiful, elegant bridge came from somewhere I wanted to escape, going nowhere I wanted to be. I didn’t get many visitors.

You have to give this all up, Ted told me. This gig is getting serious.

Sure, I said. I was at that point anyway. I was ready to flee Brooklyn and break out of this stultifying existence. He looked at me, saw me, and understood my discontent and confusion. I was ripe to be sucked into a cult, which is essentially what the Weathermen were.

For a couple of days after returning from Chicago, my mother didn’t question me about my actions. When I was sufficiently recovered, she let it drop. The FBI was here, she said. They searched the house. She pleaded with me: promise me you won’t have anything to do with those people. I promised.

To get out of my mess in Chicago, I relied fully on my white skin privileges. My father knew somebody who knew Mayor Daley and that somebody could get me out of this. I was screaming through the streets of Chicago against fascist Daley and now I needed him to fix my trial. I flew to Chicago with my father and stood before the judge, who dropped the charges (surprise surprise). It was bitterly cold, and the Chicago wind whipped through the concrete canyons. My father took me to dinner and tried to relate to me. It didn’t work. The next time you get arrested, do it in Florida, my father said. The best he could do was joke and have a drink.

I lied to my mother. A couple of months later, between Christmas and New Years, I flew to Detroit with my girlfriend to go to the Weathermen's War Council in Flint. Three days of freewheeling sex, martial arts training, and endless proselytizing about going underground and joining our brothers and sisters around the world in armed resistance. They weren’t kidding.

A few months after the War Council, Ted Gold and two others were blown up in the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion. That July, the ruling came in from the State Board of Education. I won. Now what?

Boy vs. HS Principal HAHA. Also, my grandmother's name was Shirley.

Well done young Rose!

-Dan B., Bellingham